Knowledge was once free. It used to be deeply rooted within our instinct and was instrumental in shaping our wisdom. It possessed a mystical, ineffable value. It was essential to our existence, imparting an exchange laden with insights and full of critical information; like how to read the clouds, to sense the rain, count the tides or knowing which berry to eat. It was a gift which was passed-on from generation to generation. Today we live in the age of information where knowledge is the commodity of our new economies. As we continue to expand the networks of our interconnected lives the data and information we manufacture acts as a form of currency where the feedback from our exchange implicates us in a new form of labour. The digital ‘image’ of our new economies shapes the language of our employment, an image which is far more than just a transmigratory object for the proliferation of aesthetics, politics or emotions

data

" johoka shakai "

Truth and the information society.

Pushing Pixels

"There’s a funny moment toward the end of the book when Vertesi pays a visit to a researcher named Ross, who was known throughout the Rover community for his image processing skills. Vertesi asks Ross to demonstrate his vaunted decorrelation stretch technique; a little perplexed, he opens the image processing suite on his computer, loads some sample images, and explains: “I just push this button.” The distinctive greens and purples that recalled, for Vertesi, the palette of Andy Warhol were the result of a software macro applying a mathematical formula."

Janet VertesiSeeing Like a Rover: How Robots, Teams, and Images Craft Knowledge of MarsUniversity of Chicago Press - 304 pages. April 2015

Retrieved from: http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/pushing-pixels/

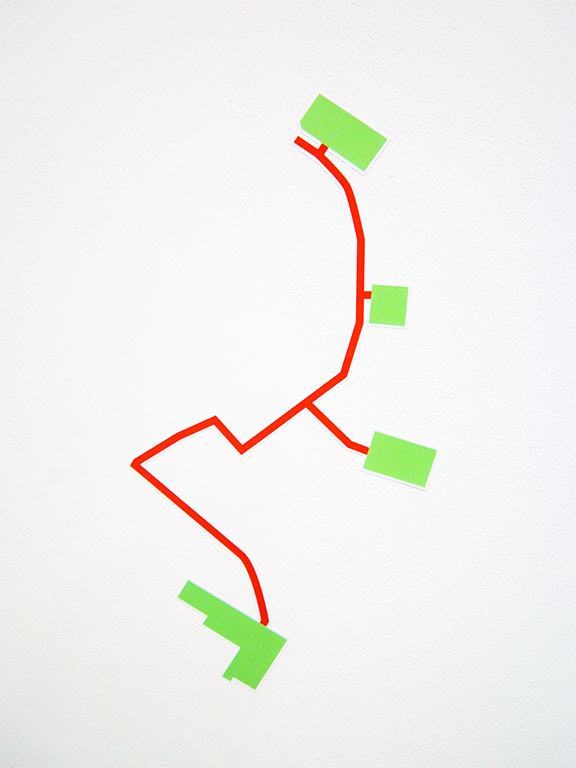

a layering of bounding boxes

[image] c.valenti - 2015

Unlocking the Mysteries of the Bounding Box

Persistent URL for citation: http://purl.oclc.org/coordinates/a2.htm

Douglas R. Caldwell

Douglas R. Caldwell (e-mail: Douglas.R.Caldwell@erdc.usace.army.mil) is employed as a cartographer and geospatial analyst at the US Army Engineer Research & Development Center, Topographic Engineering Center, Research Division, Information Generation and Management Branch, 7701 Telegraph Road, Alexandria, VA 22315.

Date of Publication: 08/29/05

Abstract

Few geospatial data representations are more basic than the bounding box; a rectangle surrounding a geographic feature or dataset. Bounding boxes are a key component of geospatial metadata and lie at the heart of many computational geometry algorithms as well as spatial indexing systems. Despite their ubiquity and common use, bounding boxes are more complicated than they first appear. The phrase that ‘spatial is special’ applies to this humble representation as well as to more sophisticated geospatial representations. This paper explores the nuances of correctly understanding, using, and interpreting bounding boxes.

Keywords: Bounding box, Minimum Bounding Rectangle (MBR), metadata, map projection, geographic information systems, GIS

The bounding box is a fundamental component of numerous computational geometry algorithms, indexing schemes such as R-trees, and metadata. As a surrogate for a feature, it provides exact information on the extent or limits of the feature and approximates the coverage. Despite its ubiquity and simplicity, the bounding box remains a subtle and nuanced entity, showing once again that "spatial is special."

http://www.stonybrook.edu/libmap/coordinates/seriesa/no2/a2.htm

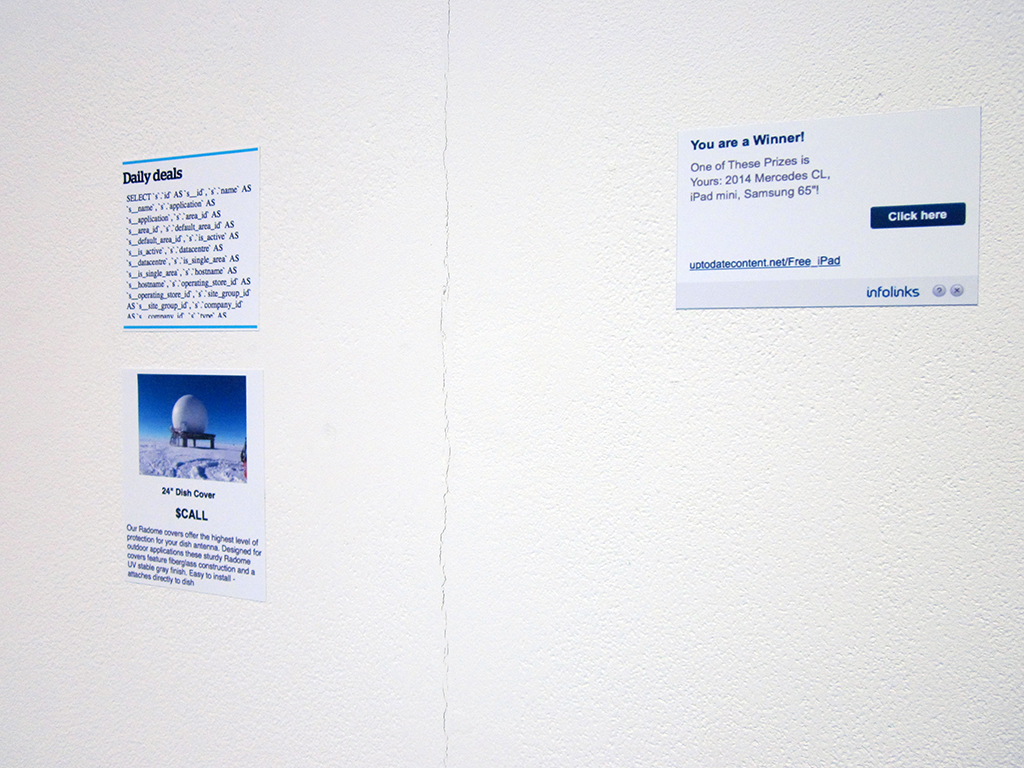

information shadows - a brief digest

updated as of : 2015.06

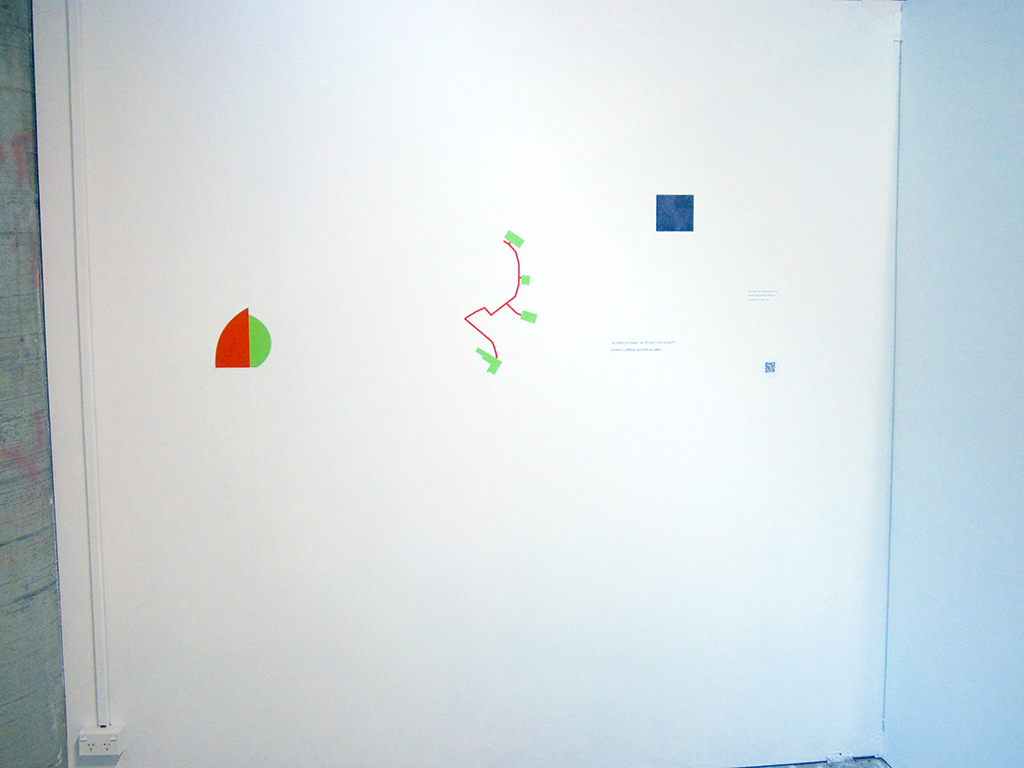

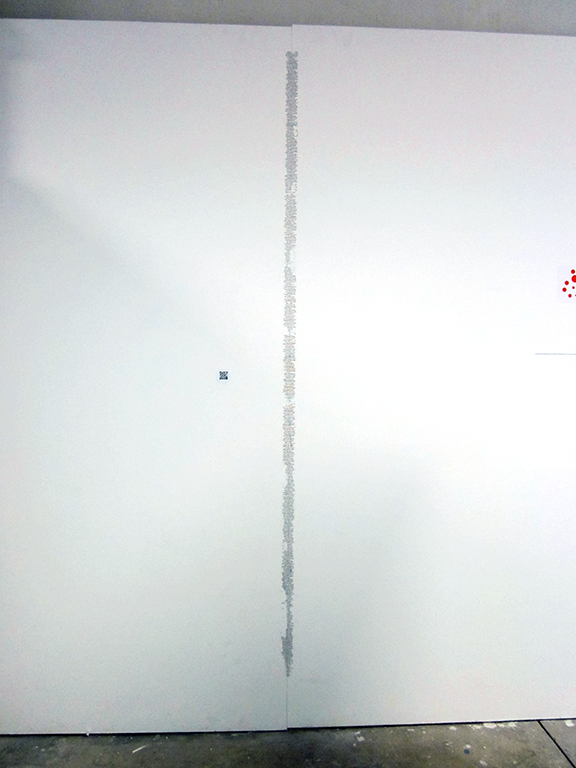

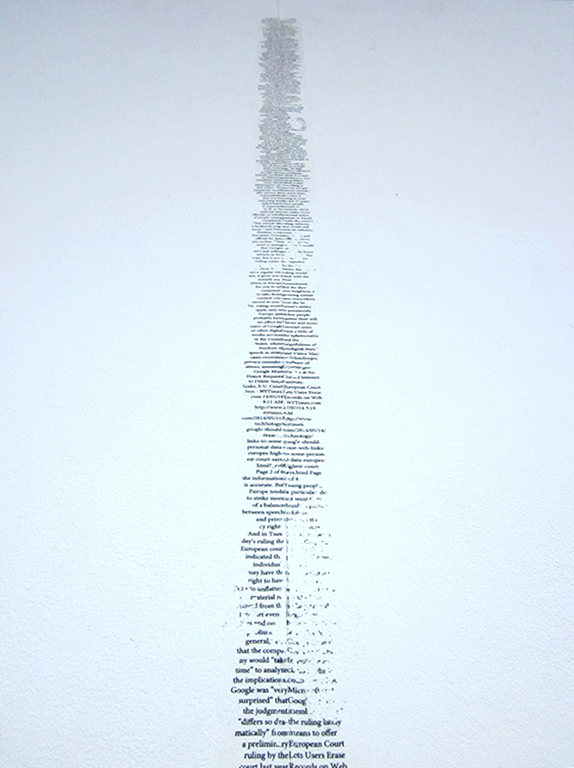

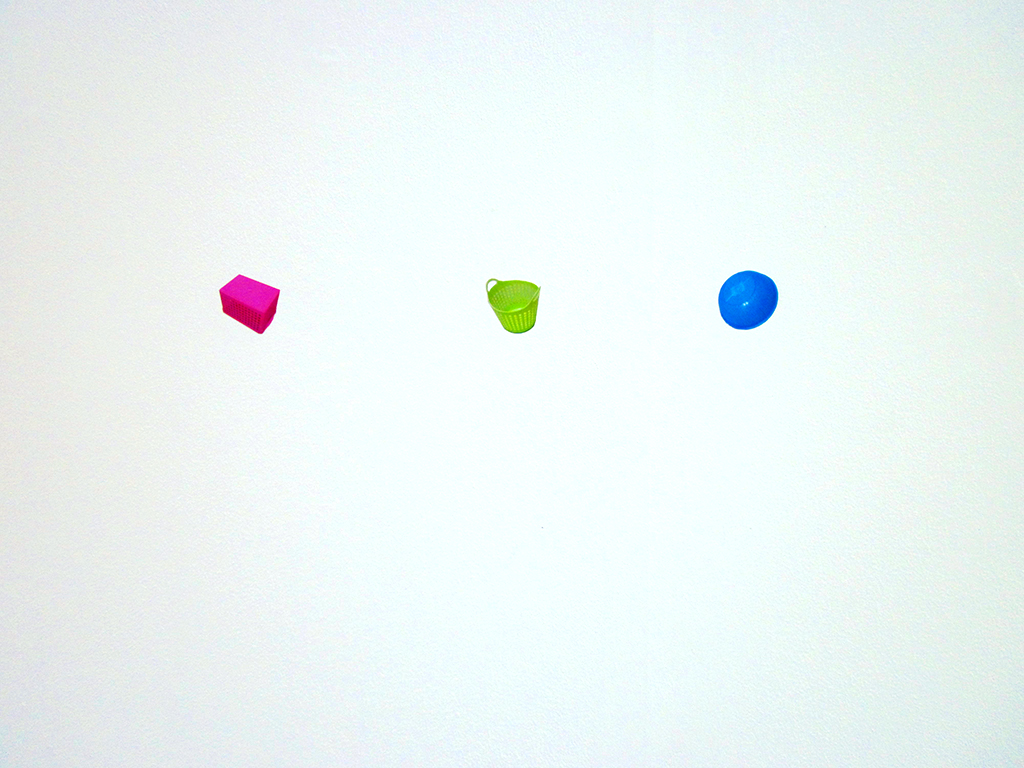

where is the interface? why can't a wall be an interface? how about a space, a void? is that not an interface? things are unfinished. some patterns seem to be emerging. talk is not about the things, object/images or otherwise, that occupy the wall but more about the ideas which surround them. the embedded meaning or rather the residual value which they impart. their place in the context of greater meaning or whether they even have a place within the space they temporarily inhabit? how to transport a viewer elsewhere? i enjoy encountering a space and making decisions in the moment. how much content to include? where should they be positioned? what is their relation to each other? is there one? a minimalist aesthetic? can one object/image carry that much weight? ...

... i was told to wait ...

images below from 'global / local' summer seminar whitecliffe college of arts and design mfa mid-course submission : 2015.02.16-22 : install at Pearce Gallery and SGBR Studio, 130 Georges Bay road, parnell, auckland

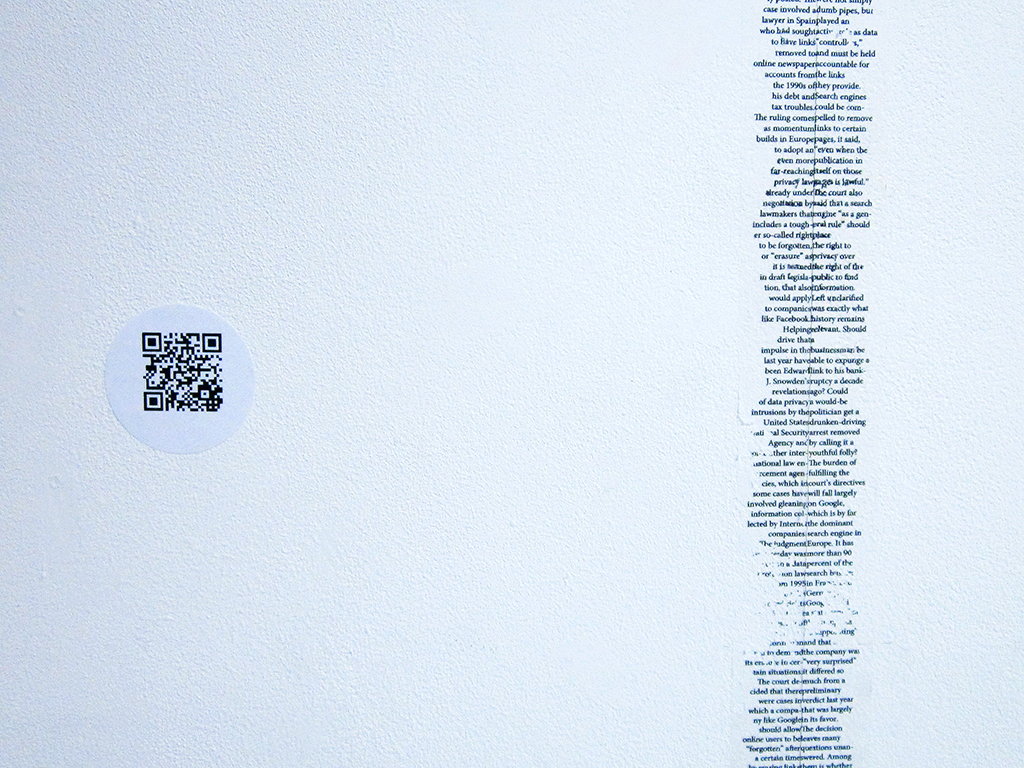

Information shadows

Our thirst for knowledge and our appetite for understanding is what has propelled humanity forward. As we continue to broaden the knowledge based economies of our interconnected lives the data and information we manufacture acts as a conduit where the content we exchange contains a new form of labour. This ‘user activated labour’ results from a transaction where the value of exchange is not immediately one of economics but rather an exchange of information ripe for harvesting. Objects and resources are embedded with an information shadow and as we engage with our data driven society we extend the value of any given resource beyond its sole purpose as a commodity. The information presented here acts as a mediating point and seeks to explore the possibilities where concepts and ideas might exist beyond the boundaries of their function and intent. The accompanying QR codes link to a digital space where ideas exist in another dimension. These black and white cryptographs act as an interface between a physical world and the digital universe.

You will need to download a QR reader to your device to scan and follow the links.

update: 2015.06

This project began as the Data Syphons project.01 on blended-theory. It has since been absorbed into the transparency in exile: eighty-eight or there abouts project. They straddle the same subject matter and as these projects continue to be refined they will migrate into more specific lines of inquiry.

tangimoana_panels

in search of data

For centuries humans have been collecting data. Ever since the first scientists, cartographers and philosophers began to question the boundaries of their existence and to explore the possibilities of the unknown, humans have been collecting, classifying and documenting their observations.

Today we continue to explore the possibilities of pushing our boundaries further outward where we extensively collect the bits and bytes of our interactions. In a series of online projects, blended-theory aims to open up a dialogue around the function of data in the contemporary; who is collecting it, what is it being used for and how might it shape us as we unknowingly participate in a world immersed in the shift to a digital existence.

/ project . 01 encouraging a culture of : remix / sampling / sharing / zero copyright.

Benjamin Tiven and Triple Canopy

[image] Benjamin Tiven, Daniel arap Moi at a Public Presentation, Unknown Date, 2013, inkjet print 20" × 25".

[image] Benjamin Tiven, Daniel arap Moi at a Public Presentation, Unknown Date, 2013, inkjet print 20" × 25".

Pixels, root properties, illusions, patterns, grids and cities

Michael Cowan, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at Carnegie Mellon University and Benjamin Tiven, artist and contributor to the online magazine Triple Canopy, engage in a fascinating conversation, titled How we see in which they discuss the role of the brain in the understanding of the sensory world. The conversation revolves around issues that relate to our visual systems and the role of consciousness, evolution, experiential and scientific influences in shaping a visual understanding.

The interview is part of Common Minds, a series of essays which investigate the intricacies of the brain and the growth of neuroscience in contemporary society and science. Interestingly, Tiven titles this interview as a collaborative work and not an interview. This approach highlights the multiple roles that artists, such as Tiven, engage in and that any discourse is as valid a piece of art work as any painting, photograph, sculpture or digital creation. Below is a short extract from that conversation:

Our monitoring of the world is really much less continuous and accurate than we think it is. Experience is the conversion of energy into data. The project of all life is to correlate the interpretation with the energy source, since the better your ability to interpret reality, the more likely you are to survive and pass on your genes. Now, how close or causal is the relationship between the energy we experience and our interpretation of it—that's a different question. In fact, something like illusion or magic is based on a discrepancy between the information we're taking in and our interpretation. (Tarr, 2013 para 15)

Corrupted imagery and heads of state

Benjamin Tiven's approach to his art work is collaborative in nature and investigative in style. He deals with the longevity of images and the cross pollination of data from its analog forms into the digitised world as a need for survival. These manifest themselves as conversations that revolve around the issues of existence, memory and the way that stories are told. In A Third Version of the Imaginary, Tiven researches the archived footage, buried in the depths of the Kenyan Broadcasting Corporation, and the events surrounding the 1973 Kenyan Independence Day parade. He brings the archived footage back to life through a series of interviews and conversations which corroborate the grainy, choppy footage from a technological past.

Employing the internet, through Triple Canopy, as a platform for the reinterpretation of these occurrences, the ‘conversations’ express themselves as investigative journalism which delve deeper into the politics of regimes past, the power of political imagery and the data that forms these events. Tiven describes an aspect of his work as the "increasing interchangeability between objects and data" and in one of these conversations with Brian Larkin, Larkin describes that a “breakdown shouldn’t be seen as the absence of something, but rather as the groundwork for something else coming into existence” (Larkin, 2014). This view exemplifies what Tiven’s work is about; that all things have data, past, present and future and in the retrieval and archiving of these events, new occurrences happen.

The digital space can now act as the repository of our actions. The increased capacity of storage through micro technologies and cloud depositories has expanded the realm of knowledge and the capacity for the instantaneous retrieval of information. The explosion of on-line magazines, blogs and social media sites has spurned an environment where all our experiences can be recorded and archived. This ever expanding environment can also be seen as the collective memory of our times.

But one day, these digital spaces might mirror the dusty archival rooms of past regimes, which means that the decoding of our digital past will require new technologies and new visionaries to retrieve them from their slumber. So, who will be responsible for the reinterpretation of these memories? Who will re-mix, loop, splice, cut and paste new story lines in an effort to uncover the deeper connections that occurred in the posting of our existence? As the digital space increasingly becomes controlled and commodified will it be the artist, the writer, the scientist or will we relinquish that responsibility to the powers that govern us? And will these interpretations represent the truth?

Reference:

Tarr, M. & Tiven, B. (2013). How we see. Retrieved from: http://canopycanopycanopy.com/contents/how-we-see

Larkin, B., Nyong’o, T. & Tiven, M. (2014). Everyday static transmissions. Retrieved from: http://canopycanopycanopy.com/contents/everyday_static_transmissions